|

Terri Evans came into my life in 2009 and left just a short while later. We found each other through our family trees on Ancestry.com. She sent a message to me saying that she was also researching Cecila Potts, her grandmother. She had been placed for adoption and was researching her birth family. I wrote back, “Well, hello cousin!” From then on, we had long message and email threads back and forth as we found out about each other’s family, growing up, siblings, and our beloved dogs.

In 2010, my husband, Don, and I drove from North Carolina to Minnesota to visit family and friends. On the way back, we stopped in Menomonie, Wisconsin to meet Terri. She working at a residential alternative home, and as we drove up, one of the residents was standing in front of the house waving at us. She rushed in to let Terri know, and I finally got to meet Terri and her dog, Scout. We stayed for coffee, and then made our way back to North Carolina. We continued our correspondence, and then in 2013, she wrote to me asking if she and her mother could come to North Carolina to visit. Her mother had taken each of her children on a trip to wherever they’d like to go, and now it was Terri’s turn. She wanted to visit me in North Carolina.

0 Comments

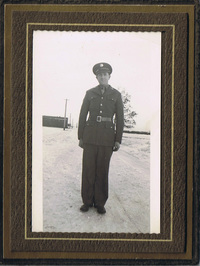

Had he lived, my father, Richard Moran, would be 100 years old today. Of course, that would have been about twenty-one years too many. With emphysema, all of his energy went into breathing, so much so that his body wasted away, his clothes hanging off of him, suspenders kept his pants up. After moving from his lift chair to wheel chair, he’d need a rest break to get his breath again before getting into his bed. On one of those evenings, after the rest breaks had gotten longer and longer, I told him that the doctor said he could have home hospice from then on and that he’d have maybe six months to live. It had taken all I had to say those words. I could barely breathe waiting for his response. He snorted, “Damn, that’s about six months too long, if you ask me.”

He was a mystery to me. There was this black hole of information about his family and his past. My grandparents had all died by the time I was one and neither of my parents talked about them, so any stories I would have heard from them were lost to me. I asked Mom about Dad’s family. “Oh,” she said, hesitating, “I don’t think he even remembers his dad.” I noticed the hesitation. “And his mom died when he was away in the service,” she finished. Something in the hesitation made me not ask again. Work never ended for settlers in the late 1800's. They fought to claim the land. Looking at a tree-filled plot, they imagined a blank canvas they could fill with full-grown crops, planted in straight lines packed to the horizon. It was optimism to see it in that landscape. They cleared it, planted and cared for the crops, and built their dreams upon the land. Their optimism was tested in 1873 when Rocky Mountain locusts descended upon Minnesota fields. Commonly called grasshoppers or hoppers, with their first appearance they devastated crops. In Mary Vance Carney's book, "Minnesota, The Star of the North," the old farmers later recalled the locusts' arrival, saying, "Sunlight, shining on the outspread wings of the insects as they flew through the air, made the swarm look like a white cloud." While I've not travelled extensively, I do love it. A fan of the Rick Steves approach to travel, when we go overseas we choose to stay at small family run hotels in the city center, and occasionally we shop for dinner at the local grocery store instead of going out to a restaurant. Other ideas I've gained from reading Rick Steves' travel guides are that it's better to spend your money on experiences rather than on high priced hotels or tour groups that insulate you from the local experiences, and if possible, save daylight for sightseeing rather than travel.

Portions of my poem, "Sleeping on the Train," were based on our experience travelling from Prague to Budapest. Saving our daytime for touring Budapest, we boarded a train at 10:00 p.m. at the Prague station. Unlike anything you might envision from Hercule Poirot's ride on the Orient Express, these sleeper compartments were a small spartan room with a window, bunk beds against one wall, a corner wash basin and a small closet behind a curtain. Comfortable enough to sleep—nothing more. While doing research for my poem, Sleeping on the Train, I discovered another gap in my education--The Orphan Trains. Between 1854 and 1929, up to 200,000 children were placed into homes across 45 states, Canada, and Mexico. Two organizations created what we now call 'The Orphan Trains' where anywhere from 10 to 30 children at a time were taken from large Eastern cities to live with families in rural areas.

A confluence of events led to a large number of homeless or destitute people in large U.S. cities like New York and Boston. A series of economic recessions and depressions in the early 1800s, changes to factory automation reducing the number of workers and apprentices needed, and a rapid influx of immigrants beginning in the 1830s vying for already scarce jobs all put a strain on existing public and private charities. Organizations like The Children's Aid Society and The New York Foundling Hospital took in children who were either abandoned by parents, found as vagrants, or were ordered by a magistrate to be placed with the organizations. |

Gail WawrzyniakGail Wawrzyniak is a North Carolina writer bringing together her love of art, history and writing. Archives

October 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed